CIC member presidents and chief academic, student affairs, and diversity officers explored a variety of strategies to enhance civic education and to improve diversity, equity, and inclusion on campus. Highlights from several plenaries, concurrent sessions, and workshops that discussed these critical topics follow.

Colleges and Universities Play Essential Role in Support of Democracy

Top Takeaways

- Colleges and universities are integral to democracy, as they work to advance social mobility, encourage engaged citizenship, defend the importance of facts, and cultivate pluralistic, diverse communities.

- To fulfill these goals, higher education leaders should advocate for government support and change practices that give unfair advantage to affluent students; infuse education in democracy into their curriculum; ensure that faculty research is transparent to the public; and bolster a stronger culture of debate and dialogue.

In the Presidents Institute address “Connected Futures: Higher Education and Democracy,” Ronald J. Daniels examined four key responsibilities of higher education: to promote social mobility, teach civic education, generate knowledge and expertise, and foster pluralism. He described reforms needed to ensure healthy futures for both democracy and independent higher education. Daniels is president of Johns Hopkins University and a law and economics scholar. His most recent book is What Universities Owe Democracy (2021).

In discussing the challenges facing democracy—nearly one year after the storming of the U.S. capital on January 6, 2021—Daniels remarked, “It was clear then and is today that a tremendous amount of work remains to sustain and nourish the democratic experiment in years and decades to come. This work must draw on efforts of democracy’s core institutions…including colleges and universities.” He asserted that higher education has been indispensable to contemporary democracy over the last two centuries. “This is especially true in the U.S.—where this nation’s diverse colleges and universities are interwoven into the fabric of democratic life. With nearly 4,000 institutions of higher education employing more than 1.5 million faculty members and educating 20 million students, there is no denying that our impact on society is profound.”

Daniels first focused on social mobility. “Colleges and universities have long been society’s most important institution for facilitating liberal democracy’s promise of mobility.” He added that although college has made the American dream a reality for many—but not all citizens, particularly those of color—“today that dream seems more elusive than ever.” The overarching cause, he said, is that “states have scaled back financial support for higher education, and federal funding has stagnated and lost focus” while “colleges and universities have adopted or doubled down on a variety of admissions policies” that benefit wealthy students and hinder low-income ones. Daniels argued that higher education leaders need to continue to advocate for government support of higher education (including increasing the Pell Grant). And highly selective colleges and universities need to either abolish or profoundly reconsider admission and aid practices that give unfair advantage to affluent students.

Second, Daniels discussed the role of college in civic education. Noting that long-term trends of civic participation “are woefully dispiriting,” Daniels said that teaching citizens the foundations of democratic life is an urgent and existential necessity. “For far too long, colleges and universities have been content to let K–12 schools bear the burden for education for democracy. We don’t have that luxury anymore.” He added that colleges should have at the center “a democracy requirement, such as a course, an extracurricular activity, or exam.” How each institution achieves that should be determined by its own history, the population it serves, and its mission. Daniels mentioned that many CIC institutions—such as Franklin Pierce University (NH), College of the Ozarks (MO), and Wagner College (NY)—have infused education in democracy into their curricula in unique ways. He suggested that it is important for democratic education programs to be even-handed, incorporate rigorous study, and “above all, provide students with the knowledge and tools to revive democracy’s promise.”

Regarding the third category, facts and expertise, Daniels remarked “Colleges have long been preservers and discoverers of facts. It is core to our mission. And the knowledge we create has become instrumental to life.” However, he noted that in recent years we have seen “cracks” and setbacks in academic research, for example if bad data is released and fuels disinformation campaigns. He emphasized that colleges and universities must ensure that the research and insights of faculty are open and transparent to the public to assure trust in science and facts.

Finally, Daniels highlighted the way in which colleges serve society by acting as “microcosms of pluralistic, multiethnic democracy that have the capacity to model for students how to interact with one another across a vast spectrum of experiences,” all of which requires interaction, dialogue, and debate. He expressed two concerns: Although “American higher education has made undeniable strides in expanding access and addressing inequities, the process has taken far too long and remains unfulfilled,” and “we have not fully or adequately fostered in students a capacity for differences that are foundational for healthy democracy.” In one example he said, “We have become too reliant on speakers who are in broad agreement with one another”…. “committing ourselves to more disagreement in our public events is one way we can model the art of debate and the important value of civic friendship.”

He closed by asking, “On this somber anniversary of the capital insurrection, how can we do anything other than reaffirm in word and deed our commitment to an idea that is so profoundly connected to freedom and equality?”

This plenary address was the inaugural “Richard Ekman Keynote Address in Higher Education.” The CIC Board of Directors established the address in 2021 to recognize president emeritus Richard Ekman for his more than 20 years as president of CIC. Each year, the Ekman Address will be delivered at the Presidents Institute by outstanding scholars, thought leaders, or practitioners.

U.S. Democracy Is Contingent on Addressing Structural Racism

Top Takeaways

- Higher education leaders have a responsibility to identify and address structural racism on campus.

- Campuses should include in their curricular offerings strong history and Black, ethnic, and Indigenous studies programs and focus on hiring and advancing diverse faculty members and administrators.

- Colleges and universities should teach their students lessons from the past so they can help end problems that threaten democratic society, including racism.

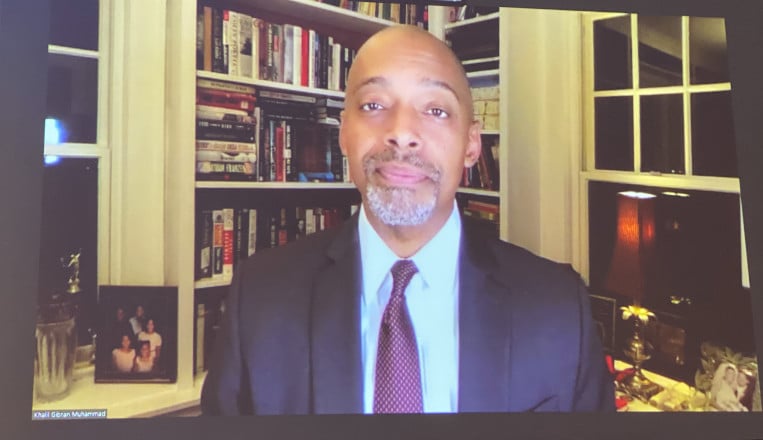

Presidents Institute keynote speaker Khalil Gibran Muhammad underscored that racism is a threat to democracy, urged educators to prepare students to meet the challenge of racism, and called on participants to address structural racism on their own campuses. One of the nation’s leading historians of race and racism, Muhammad is the Ford Foundation Professor of History, Race, and Public Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School and director of the Institutional Antiracism and Accountability Project.

With the one-year anniversary of the January 6 insurrection looming, Muhammad, like Daniels, tied his presentation to the attack and its aftermath. “It’s a debate about replacement theory and critical race theory. And I’d be willing to bet that most of the institutions of higher education and higher learning represented in the room today haven’t been preparing most, many, or even more than a token few of their students to rise to meet this challenge. I hope that doesn’t feel condemnatory, because it certainly is reflective of my own experience as well.”

Muhammad cited work by the Southern Poverty Law Center that highlights the exceedingly low percentage of high school students who can identify the Brown v. Board of Education decision or who know that slavery was the central cause of the Civil War. Emphasizing the importance of learning from the past, he said he has “observed how powerful this reckoning with our history is and how powerful it is to teach it to our students, to empower them with the scientific knowledge they need to diagnose the conditions that ail the very democratic institutions that we depend upon.”

Regarding college curricula, Muhammad highlighted the importance of offering strong Black, ethnic, and Indigenous studies programs and cautioned that fields such as African American studies frequently seem like “stepchildren in higher education.” He said that administrators may justify underinvestment in African American studies by pointing to a small number of majors, lower citation counts, or mixed teaching reviews, but that underinvestment conveys that the university devalues the field and by implication that it might also devalue Black lives. He said that using strictly market-driven factors to make decisions can lead to results that “are in stark contrast to the values most of the institutions in this room…claim as their core values.”

Muhammad shared how once when he was serving on a hiring committee for a senior scholar to run a criminal justice program he realized that the form letter sent to reviewers to assess the tenured candidate pool didn’t list people from the fields of ethnic studies, African American Studies, or critical race studies. “In other words, the very fields that had been central to understanding how systemic racism works in the criminal justice system, were not reflected in the evaluation process itself…. If we are not mindful that the history of exclusion, of excluding these fields at least up through the 1970s and 1980s, isn’t actively and intentionally redressed in our day-to-day practices, then these traditions of exclusion will simply continue.”

So, what should college and university leaders do? “University leaders can’t solve for these problems simply with access and affordability. They actually have to help solve for a system [systemic racism] built by design to exploit and extract from some, for the benefit of others,” Muhammad said. “People ask me all the time, ‘what’s the best intervention?… What data are you using?’ And the truth is, we don’t have great answers to these questions, because despite 50 years of so called post-civil rights advancement, most people in higher education [and other sectors] were not solving for systemic racism…they were solving ultimately for individuals’ skill acquisition and access.” So what leaders should do today, he said, “is to continue identifying how these systems work, how they are sustained, how they mutate, and shape shift, and also to learn how people are developing tools and writing new policies, practices, and procedures to change things to re-wire the circuits and transform our institutions.”

Muhammad concluded by saying that “We can make it plain to the youngest of citizens and newcomers alike that U.S. democracy is in fact, contingent on learning from the past, not overcoming it.”

Classical Scholar Challenges Colleges to Build More Inclusive, Antiracist Institutions

Top Takeaways

- Western higher education and humanistic fields, such as classical studies, have complex roots that may not seem welcoming to all students.

- Higher education leaders should reconceive their institutional designs to build more inclusive, antiracist campuses.

- Colleges and universities should foster the free exchange of ideas, but offering tools to evaluate those expressions may be advisable.

The Institute for Chief Academic Officers keynote address, “Revitalizing the Humanities for Social Justice and Civic Engagement,” was delivered by Dan-el Padilla Peralta, author of the autobiography Undocumented: A Dominican Boy’s Odyssey from a Homeless Shelter to the Ivy League (2015). Peralta is associate professor of classics at Princeton University, where he also is affiliated with the program in Latino studies.

Peralta’s much-published views on how to revitalize the humanities have sparked both academic and popular discussion and spurred debate about how classical texts and humanistic learning can engage the full range of today’s students, preparing them for their lives and careers. He argues that to reverse a decades-long decline in enrollments, programs in the humanities should focus on pressing problems such as xenophobia and racism and on promoting social justice and civic engagement.

Although Peralta is a strong advocate for the liberal arts who loves “to proselytize for classics and the humanities,” he condemns ways that some classical texts justify slavery, race science, and colonialism. He argues that the study of classics is wrapped up in the racial history of America and has embedded racism throughout Western higher education. Peralta remarked that, “It does require pretty hard work to re-conceive the institutional designs of the places we work.”

Peralta shared efforts to make institutional design changes that have occurred at Princeton since summer 2020, when racial-justice protests were unfolding across the nation. In June 2020, the president of Princeton University issued a call to the university leadership and community to confront the realities and legacies of racism at every level of the institution and charged the cabinet to explore how the university could more effectively fight racism.

In response, Peralta and three other faculty members drew up 48 proposals for reform, collected over 300 signatures, and on July 4 presented them in an open letter to the university leaders. Peralta elaborated, “What we decided to do was draw up a letter that introduced our collective vision both of the pervasiveness of anti-Black racism and what we saw as our employer’s responsibilities to confront it.” The letter began with “the beating heart of the proposals,” which included demands such as “Give seats at your decision-making table to people of color who are actively antiracist and inclusive in their practices,… acknowledge the invisible work that faculty of color are compelled to do,… redress the demographic disparity on Princeton’s faculty immediately and exponentially by hiring more faculty of color,… educate the Princeton University community about the legacy of slavery and white supremacy, … and above all, lead. Show our peer institutions, and the world, that genuine service to humanity begins with dismantling the unnatural and immoral hierarchies that universities have long perpetuated, both actively and in their inaction.”

What was the outcome of the faculty letter? Although the letter “immediately elicited all kinds of criticism” Peralta said, it also helped spur several positive developments. “It is clear that the university is moving forward to pick up some of the recommendations, and some have begun to be implemented.” He referenced the university’s first Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Annual Report, which was released in October 2021, as well as a new initiative, “To Be Known and Heard: Systemic Racism and Princeton University,” which culminated in a virtual gallery and panel. Princeton continues to send updates on its numerous, ongoing initiatives to combat systemic racism.

He concluded by discussing a 2021 article “Oppressive Double Binds” (which are “choice situations where no matter what an agent does, they become a mechanism in their own oppression”) by Sukaina Hirji of the University of Pennsylvania. Peralta said, “I was looking for a vocabulary that could furnish me with lexical and semantic tools for better understanding some of the predicaments that I, as a first-generation immigrant faculty of color, found myself in. And I kept coming back to this article, because it does a good job at explaining why some of us feel motivated to try to initiate institutional and infrastructural change at our institutions even in the knowledge that such efforts at change may imperil our possibility to remain at these institutions, could jeopardize our material and psychological well-being, and might not even yield meaningful results in the long run.” He encouraged Institute participants to consider the article as they returned to their institutions.

At the end of Peralta’s presentation, CIC President Marjorie Hass remarked, “The presentation speaks so deeply to what we are facing on our campuses and in our county as we try to wrestle with the question of what diversity and inclusion looks like when it isn’t just on the margins, but when it moves itself into the center of our institutions…. Not that all of us in this room agree or need to agree, but the open free exchange of ideas like this, our ability to raise these conversations to teach about them, to stand in the face of the anxiety and discomfort it engenders in many of us, that power and freedom which is at the heart of a liberating education—we are the guarantors of that.”

Panelists Debate How to Strengthen Humanities for a New Majority

Top Takeaways

- The humanities can be brought to bear on the questions faced by people of all circumstances and identities.

- Class is embedded in the historical concept of the liberal arts: For Aristotle, being “free” meant both being free from enslavement and being freed to study by the labor of enslaved people.

- The digital humanities and public humanities create relevance and visibility for core disciplines.

Panelists in this Institute for Chief Academic Officers session—all CAOs who are also humanities scholars—responded to a question posed by moderator S. Georgia Nugent, president of Illinois Wesleyan University and former president of the Society for Classical Studies: “What does the classic humanities tradition mean to a new majority student?” She noted that “the word for leisure in Greek is the root of the word “school. Those who study are those who have the leisure to study.” Are the humanities only for privileged elites?

Sarah Fatherly, provost and vice president for academic affairs at Queens University of Charlotte (NC), suggested that digital humanities and community-centered engagement “make the work of the humanities relevant to a history of enslavement and exploitation.” Such projects give the humanities new “relevance and visibility.”

Aaron Kuecker, provost of Trinity Christian College (IL), noted that the humanities ask “what it means to be called to be a full human being” in any condition of class, race, or ability. These questions lead to the discovery of vocation; Kuecker cited CIC’s Network for Vocation in Undergraduate Education (NetVUE) initiatives as helping his campus connect the humanities and career development through the concept of vocation. He also argued that studying the humanities “teaches us to care about projects not our own,” an essential foundation of a commitment to diversity.

The Dominican faith tradition, with its concepts of “flourishing” and “dialog,” inspired general education reform on his campus more than two decades ago, according to Sean O’Connell, vice president for academic affairs and dean of the faculty at Albertus Magnus College (CT). The humanities are essential to helping “students ask their life and death questions, not the ones we as faculty think are important” as they explore vocation. He noted that too often, education of working class people has been “education for conformity,” and that a humanistic education encourages true individualism.

Workshop, Session Address Presidential Leadership for Diversity

Top Takeaways

- Presidential leadership is essential to the success of antiracism initiatives.

- Although advancing diversity, equity, and inclusion presents some ubiquitous challenges, institutional history and location

do matter. - Institutions should focus on a manageable number of diversity initiatives and anticipate that DEI efforts may progress at different speeds.

The role of presidential leadership in sustaining effective diversity initiatives was the theme of both a concurrent session (“Strategies for Diversity and Inclusion at Predominantly White Institutions”) and a workshop (“Becoming Antiracist Leaders of Antiracist Colleges and Universities”) at the 2022 Presidents Institute. Although the sessions addressed two distinct aspects of the theme, the conclusions were the same: First, the movement toward greater DEI is both a personal and an institutional journey, and not everyone moves at the same speed. Second, diversity and antiracism are about “decisions you need to make every day.” Third, “you can’t outsource [diversity] work; it has to be presidential work.” These quotations from Hollins University President Mary Dana Hinton (VA) and Oberlin College (OH) President Carmen Twillie Ambar capture sentiments widely shared by participants.

The workshop, led by Hinton and Augsburg University (MN) President Paul Pribbenow, grounded the contentious term “antiracism” in a working definition: “the active process of identifying and eliminating racism by changing systems, organizational structures, policies and practices, and attitudes, so that power is redistributed and shared equitably.” Personal dimensions of antiracism may include a reckoning with your own racial identity, the “courage to listen and learn,” and the “courage to educate your community.” Pribbenow described the intersection of institutional mission and the imperative of antiracism: For example, as a university in the Lutheran tradition, Augsburg already has a commitment to hospitality and justice; as a liberal arts college, it should be committed to “giving our students today an opportunity to learn about their own lived experience and identity.” The goal, one workshop participant added, is to be able to say “these are our values, and they apply to everyone.”

Presenters turned to specific “equity-minded” policies and practices. At Hollins, this began with refocusing the “burden for change” away from students and toward the president, senior staff, and trustees. At Augsburg, a campus-wide planning process began with a presidential call for “500 ideas on diversity and inclusion” and ended with a multi-year, inclusive equity initiative that was embedded in the university’s larger strategic plan. The strategic framework was made operational through four general recommendations for action and a number of specific programs to support culturally relevant instruction (for example, antibias training for faculty and staff members and the development of a new diversity and inclusion certificate program), to promote the institution’s “equity voice” (for instance, an audit of all student-facing communications to identify inadvertent biases), and to strengthen the university’s role as an anchor institution in the larger community, among other goals.

The concurrent session on strategies for diversity and inclusion began with the unique circumstances of three distinct campuses and moved toward advice that could be applied to any institution.

- Oberlin College in Ohio has a strong legacy of abolitionism and student activism. Its challenge is to consolidate a historic commitment to diversity—now institutionalized in multiple academic programs, co-curricular initiatives, and diversity committees—and refocus on issues of campus climate and culture. As Ambar put it, “when too many flowers bloom, they hide the garden.”

- Wingate University in South Carolina has historical ties to the enslavement of African Americans (a subject of recent historical controversy) and only integrated in the 1960s. Active recruitment has increased the diversity of the undergraduate population significantly, but “diversifying students is easier and faster than diversifying the faculty and staff,” noted president Rhett Brown. Wingate has revamped the hiring process for faculty and staff members to attract more diverse pools of talent, among other measures.

As president William Craft put it, Concordia College in Moorhead, Minnesota, is located between “the history we are facing” (a graveyard where many of the Scandinavian Lutherans who founded the college are interred) and “the history we are trying to catch up with” (a local elementary school where students come from homes where nearly 100 languages or dialects are spoken). The college’s most significant and public initiative is currently the “Just Futures Reparations Project,” which focuses on the intergenerational traumas inflicted by Native American boarding schools.

Beyond these rich case studies, the session leaders offered practical advice: Focus on a manageable number of diversity initiatives (Brown suggested that “five top issues” was optimal). Make sure that the leaders of diversity initiatives are “people with budgets and responsibility.” Recognize that different parts of an institution may face different diversity challenges. Take advantage of all your resources: At different times, board members, student leaders, faculty members, alumni, or others, may be the most important drivers of change. And don’t be discouraged by the “inevitable ebbs and flows in your efforts.”

Faculty and Staff Can Advance Antiracism Objectives

Top Takeaways

- Antiracism starts at the individual level, but it has the greatest impact at the institutional level.

- Collaboration is essential to the success of equity, diversity, belonging, and inclusion initiatives.

- Institutions should take advantage of the expertise they already have on campus as well as prioritize the hiring of additional diverse faculty members.

- Hiring for diversity is not enough; new and existing faculty and staff members all need support to promote antiracism.

“Promoting Antiracism on Campus,” a session at the Institute for Chief Academic Officers, focused on building the capacity of faculty and staff members to support an institution’s antiracist objectives. Leanna Fenneberg, vice president for student affairs at Rider University (NJ), set the tone for this session with a reminder that “antiracism starts at the individual level, but it has the greatest impact when it is prioritized at the institutional level.” She was joined on the panel by DonnaJean Fredeen, Rider’s vice president for student affairs, and a pair of senior leaders from St. Norbert College (WI), Jennifer Bonds-Raacke, provost and vice president for academic affairs, and John W. Miller Jr., dean of curriculum and senior diversity officer.

The panel identified four specific strategies to promote antiracism:

- Institutionalizing a commitment to antiracism by making antiracism part of the ongoing strategic planning and evaluation cycles. At Rider, for example, a collaborative campus team defined six specific goals (such as increasing the diversity of employees) that were closely mapped to an existing strategic plan and included measurable benchmarks. Although the most effective plans are typically led (or endorsed) by the president’s office, Fenneberg argued that

any administrator can start by “creating [an antiracism] plan at whatever level of control seems relevant to your position.” - Bridging academic and student supports. St. Norbert’s Miller embodied this strategy, having been hired through an atypical job search for a chief diversity officer who would also serve as a senior academic officer with significant curricular responsibility. As he noted, “very few pockets of authority don’t intersect on campus, so it was very exciting [and important that] I did not have to set aside my faculty role.”

- Faculty cohort hiring. “You can diversify your faculty,” said Fredeen, “but it takes the will and courage to do so.” At St. Norbert, a clustered search for 13 new faculty members across nearly as many departments, where every job description includes an explicit preference for research and/or “lived experiences,” has supported the diversity goals of the college.

- Developing faculty and staff. Expert speakers from outside the institution, faculty reading circles, campus-wide “big reads,” panels and workshops that draw upon internal expertise, and additional resources for professional development can all help faculty and staff members promote antiracism. Fredeen pointed out that this means prioritizing the work of antiracism in budgeting—for example, by shifting extra resources to a center for teaching and learning if you expect its staff to develop and lead additional training sessions on inclusive pedagogy.

Chief Officers Examine Design of Campus Diversity Education Plans

Top Takeaways

- Campus leaders should ask, “Who needs to be at the table to successfully launch a diversity and inclusion education plan?”

- Those responsible for creating, shepherding, and implementing campus diversity plans must be in the room with senior leadership.

Chief academic, student affairs, and diversity officers explored “How to Design a Campus Diversity Education Plan,” in a workshop led by Donnesha A. Blake, director of diversity and inclusion at Alma College (MI), and Danyelle Gregory, director of multicultural student services at Ferris State University.

Blake raised the issue of unconscious bias within academic spaces. Leaders must not only understand personal biases about individuals, but also how institutional policies and procedures may be perpetuating unconscious biases. Gregory discussed the importance of learning outcomes in any training to ensure the institution is addressing needs and seizing opportunities.

Participants completed an exercise to help them identify the depth of work needed to develop an effective diversity education plan. Learning outcomes, stakeholders, and resources can be analyzed to assess whether institutions are in more foundational or advanced stages of preparedness.

The central point the facilitators made was that those responsible for creating, shepherding, and implementing campus diversity plans must be in the room with senior leadership when planning and implementation are discussed. This is imperative because, while some institutions have begun bringing chief diversity officers into the senior leadership level, those charged with implementing diversity education plans are often not at the senior leadership table. Leaders must ask, “Who needs to be at the table to successfully launch a diversity and inclusion education plan?”

Equity by Design: How Design Thinking Can Transform Decision Making on Campus

Top Takeaways

- Design thinking is a “human-centered and design-focused methodology to solving problems” that offers collaborative alternative to top-down decision making.

- The design-thinking model has been adapted for colleges and universities, with a particular focus on integrating equity into each stage of the process.

- Planners should ask such questions as “whose voices should be present in the planning process?” and reflect on whose voices are being prioritized.

Successful companies, such as Apple, Microsoft, and Nike, have for some time used design thinking to foster collaboration and innovation. In 2021, the Pullias Center for Higher Education at the University of Southern California adapted the design thinking model for colleges and universities, with a particular focus on integrating equity into each stage of the process. During a Presidents Institute workshop, two co-authors of this report partnered with a CIC president who has used design thinking for strategic planning to introduce this model and its benefits for CIC member institutions.

KC Culver, senior postdoctoral research associate, and Jordan Harper, research assistant, both at the Pullias Center, introduced the Design for Equity in Higher Education model. Design thinking offers a collaborative and human-centered alternative to top-down decision making. The model includes eight phases, starting with Organize (the formation of a design team and its objectives) and culminating in Test (the implementation of the solution, followed by evaluation and revision). Culver and Harper noted that some elements of design thinking had to be adapted to suit the distinctive environment of higher education. For instance, they added step seven, Build Consensus, to take into account shared governance at colleges and universities.

Kevin Ross, president of Lynn University (FL), demonstrated how design thinking brought together representatives from the entire Lynn community, including faculty and staff members, students, donors, alumni, trustees, and parents, to create the 2025 strategic plan. He credits design thinking for the shift to a block schedule during the pandemic and the creation of a resiliency toolkit for students. He noted that this model has filtered down to become part of departmental decision making, too.

A mini-exercise helped presidents put the Design for Equity model into practice, focusing on the question of how to build more diverse boards of trustees. Culver and Harper walked them through the process to develop a variety of ambitious solutions and insightful questions.