The COVID-19 pandemic, economic downturn, and many other recent developments have underscored the importance of campus collaborations—from working with boards of trustees, to cooperation across departments and roles, to external partnerships, and more. Presenters at both the Institute for Chief Academic Affairs and Presidents Institute shared strategies to strengthen collaboration and partnerships.

Build the Future Campus and Define the Presidency

Top Takeaways

- Recent events have driven new levels of collaboration across professional disciplines.

- Clear understanding of respective roles and expectations is necessary for effective collaboration.

- Campus leaders and their campus partners should work together to create a sense of belonging for all students.

- To establish an effective and collaborative presidency, presidents need to be able to work across differences in identity and perspective and to build trusting relationships quickly.

Plenary panels at both of CIC’s annual Institutes emphasized the imperative for leaders in a range of campus roles to collaborate in powerful new ways to build healthy futures for their institutions.

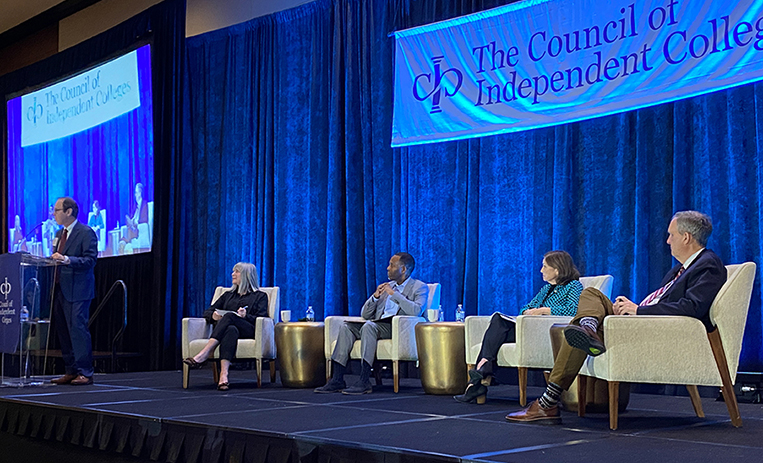

In the final plenary at the Institute for Chief Academic Officers, moderator Kevin Kruger, president of NASPA–Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education, led a discussion among a chief student affairs officer, a chief diversity officer, and a chief academic officer on how their roles have evolved in complementary ways in response to developments on their campuses.

Kruger opened the discussion by noting that recent events have driven the development of new levels of collaboration across professional disciplines. These include the COVID-19 pandemic, the emergence of new structures for advancing DEI, the increasingly pressing mental health needs of students, and a new emphasis on the role of shared governance in institutional success.

Leanne M. Neilson, provost and vice president for academic affairs at California Lutheran University, noted that the pandemic made it clear that many campuses lack strong and effective shared governance processes for decision making. In the past, a lack of clarity about the relationship between board authority and the faculty’s shared governance role had often been negotiated through lengthy and time-consuming consultation and deliberation processes. The pressure of time and urgent questions of the pandemic forced institutions to recognize and engage conflicting expectations and understandings. To address this issue, California Lutheran created a task force charged with developing a decision authority matrix. It charts which constituencies on campus had the authority to approve, to decide, to recommend, and to have input on specific issues. She noted that the key to effective and efficient collaboration is clear understanding of respective roles and expectations. She also noted that collaboration is often born of the realization that campuses need “to do things differently rather than need to do different things.”

Monica M. Smith, vice president of diversity, equity, and inclusion at Augustana College (IL), pointed out that academic and student affairs offices have long been central hubs for students, but multicultural or diversity offices have increasingly become hubs for BIPOC students. “These were the places that were made for them,” she noted. As demographic changes affect the composition of student bodies, it becomes increasingly clear that many areas in higher education underserve students of color, who then turn to diversity or multicultural offices and centers for support. Specifically, the ranks of administrators and faculty members generally remain less diverse than do student bodies. It is essential for collaboration between diversity offices and both academic and student affairs to demonstrate solidarity in support of students of color. A vigil on her campus was collaboratively organized by student life, diversity, community police and campus safety, and academic affairs professionals to ensure a holistic campus-wide expression of commitment.

Eva Chatterjee-Sutton, vice president of student life and dean of students at Washington & Jefferson College (PA), argued that it is urgent that campus leaders collaborate in a brand-new way. She urged that collaborators aim for “transformative, rather than transactional” partnerships to ensure that all students on campus experience a sense of belonging. In one example, she described how partnership with enrollment teams can help leadership teams know their students better. Enrollment professionals can contribute valuable insight into where students come from, what they bring to campus, and what transitional issues they encounter. Similarly, residence life staff have insight into how students are experiencing either belonging or alienation outside the classroom. Finally, Chatterjee-Sutton noted that social media makes it harder for students to “go to” college. Home and their former social networks come with them on their phones, permeating the “campus bubble” that former generations experienced. She challenged all present to consider what they and their campus partners could stop doing to focus on creating a sense of belonging for all students.

In the plenary panel at the Presidents Institute, CIC President Marjorie Hass moderated a conversation among sitting college and university presidents about how the presidency has changed, how they have navigated change through their own careers, and what they expect the future of the presidency holds for those who aspire to the office. The ability to work effectively across differences in identity and perspective was a central theme of the conversation.

Opening the session, Hass noted a recently published list of the “essential skills” a college president needs. This list included business acumen, strategic planning, strategic communication, crisis management, and relationship and emotional intelligence skills. Hass added, however, that in previous generations such a list might well have included quite different criteria, including perhaps academic excellence, wisdom, moral stature, and religious devotion. She wondered if all of these characteristics are still relevant.

Chip Pollard of John Brown University (AR) remarked that even 20 years ago there was “more time for a new president to get up to speed” and to build relationships with faculty members, trustees, donors, alumni, and community leaders. He added that when he started out there were also “still facts”; without agreement as to facts, building collaborative relationship to advance the institution is much more difficult. For these reasons, he agreed that the ability to negotiate sensitively across differences and to build trusting relationships quickly is essential to an effective and collaborative presidency.

Isiaah Crawford of the University of Puget Sound (WA) spoke of the importance of mentoring aspiring presidents. He also, however, reminded listeners of the “put on your own mask first” principle: It is difficult to nurture relationships with others unless leaders care for themselves as well. Collaboration and relationship building requires self-care and thoughtful attention to maintaining “equilibrium and well-being.” He recommended that presidents seek out “one hour a day, one day a week, one month a year for self-care” in order to best build the relationships on which healthy institutions depend.

Debbie Cottrell of Texas Lutheran University noted that regional realities can contribute to the challenges of collaborating across constituencies, as presidents negotiate sometimes-fraught relationships among important community partners with differing views, even as community engagement and regional relationships have never been more important. As a proud Texan, she has learned that investing time in both local and regional communities pays off, and that close relationship with nearby colleges and universities who are working in the same regional context can be extremely helpful.

Shared Governance Changing under Pressure

Top Takeaways

- Shared governance is not shared decision making; in a crisis, presidents need to be able to make decisions quickly.

- However, building trust and consensus among campus constituents and communicating robustly are critical to navigating uncertain circumstances.

- Having data and anecdotes ready can help educate trustees and other campus constituents on important issues.

Campus leaders have been grappling with how to maintain shared governance structures while improving their ability to make critical decisions rapidly. Two sessions at the Presidents Institute explored how to rebuild trust and relationships with the board of trustees and how to best guide board decision making in this era of constant change.

Campus leaders need to “continue the ethos of shared governance during this time of a rapidly changing higher education landscape, but the ability to respond quickly to crises is critical,” said Pamela J. Gunter-Smith, president of York College of Pennsylvania, who chaired a session on “Shared Governance: Rebuilding Trust and Important Relationships.” Presidents Steven DiSalvo of Endicott College (MA), Richanne Mankey of Defiance College (OH), and Elizabeth Stroble of Webster University (MO) described diverse solutions in addressing the pandemic and racial tensions during the past two years, but all agreed that building trust and consensus among campus constituents and communicating robustly were critical to quickly navigating uncertain circumstances.

Mankey and her leadership team developed a collaborative process that included an incident command team, daily meetings, and task forces “to better understand what various campus constituencies were thinking and to put change into place.” For example, “to get the board engaged, we used generative conversations to educate them on important issues” and to manage contentious faculty members, “we invited them to share what they were thinking and seeing, included them in strategic conversations, and were open to hearing disagreements.” She emphasized the “importance of communication to manage ambiguity and uncertainty.”

Webster University similarly established a number of task forces, policy groups, and working groups to develop official university policy that was constantly posted on the website and updated. “Communications have been hugely important. During the last academic year, we distributed 41 urgent or emergency communications,” Stroble said. The task forces also served a vital purpose, by “slowing down the rate of meetings [that ballooned early in the pandemic]. These structures will serve as models going forward to make policy,” she said.

Taking risks and addressing revenue issues was DiSalvo’s strategy at Endicott College in managing decision making during the pandemic. He advised that “shared governance is not shared decision making—we need to be able to make quick decisions without getting bogged down in battles over process. This is going to be a critical issue going forward.” Endicott decided early in the pandemic to continue to pay all employees with no layoffs or furloughs, continued providing a full match to 401Ks, and honored faculty salary increases per contract. “These decisions on benefits earned us a tremendous amount of goodwill among the faculty and was the key to reopening.” DiSalvo said Endicott was able to be generous because of its unique business model. The campus earns auxiliary revenue from weddings as well as from their conference center and Wylie Inn with 99 rooms. “Campus leaders can think about new streams of revenue to gain additional leverage,” DiSalvo said, and also take some risks. “Some schools with large endowments made the decision to shut down because of the pandemic. We couldn’t do that, so we took a risk and stayed open.” As a result, campus tours resumed, “which allowed us to recruit our second-largest class ever. Students and families loved that there were people on campus during the tours, unlike at other campuses they visited. This drove our numbers up.”

In a second session on shared governance (“Guiding Board Decision Making in an Era of Constant Change”), moderated by Thomas Hellie, co-director of CIC’s Presidents Governance Academy and president emeritus of Linfield University (OR), presidents Christopher Holoman of Centenary College of Louisiana, Kathleen Murray of Whitman College (WA), and Michele Perkins of New England College (NH) described several approaches—honed over the last two years—that have proven effective in working with boards, especially when decisions need to be made quickly.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the Whitman College board of trustees pushed hard to confront the larger budget issues immediately, said Murray. “We conducted a broad-based sustainability review and a strategic planning effort and ultimately agreed on three working groups—academic programs and support, student support, and administrative units. Faculty, staff, and trustees were added to the working groups.” Every group had four criteria for review: centrality to mission, enrollment, revenue, and strategic priorities. Although meetings of the working groups were often contentious, Murray said all members unanimously endorsed reports to the board, and the board was engaged throughout the process. Final decisions included making reductions in the operating budget, eliminating non-tenure-track positions, leaving vacant tenure positions open, and reducing staff through attrition and reassignments.

Holoman said the dynamics of the pandemic changed decision making at Centenary. “It allowed us to break away from a cumbersome decision-making process; we learned how to move faster by shedding older practices.” With an “ongoing, indefinite, uncertain crisis such as a pandemic, leaders must establish a vision and work toward it,” he said, while cautioning that other crises, such as major campus protests triggered by the murder of George Floyd, “require more board development and education.” Campus leaders need to remember that “the academic arena is not the water that trustees swim in every day; we can’t take for granted that they know” the intricacies of campus life and decision making “and we have to be prepared for pushback from the board.” He suggested that having data and anecdotes at the ready can help educate the trustees on important issues.

Gaining the trust and support of the board of trustees is critical for timely decision making, said Perkins, who serves as co-director of CIC’s Presidents Governance Academy. “The board was prepared to make quick decisions during the pandemic, but was initially reluctant to support new initiatives.” She made the case that “educated risk-taking is essential, and that making no decision is the biggest risk of all.” Perkins restructured the board agenda “for more engagement, brainstorming, and problem-solving. We don’t want them going into the weeds, so we present problems with possible solutions.” As a result, New England College successfully launched online programs, implemented an early retirement program, merged with the New Hampshire Institute of Art, and launched a three-year nursing program.

Other suggestions during the session’s Q&A included restructuring committees to align with the work of the college, diversifying the board, revising bylaws to make the board more strategic and less operational, hosting in-person retreats to focus attention on a few strategic priorities, and ensuring that the board chair assumes three roles: boss, mentor/collaborator, and friend and ally.

Chief Officer Teams Help Students Ponder Their Futures

Top Takeaways

- Students respond well to both curricular and co-curricular opportunities to think about their future directions in life and explore their callings.

- Campuses can implement a focus on calling and vocation in various ways, depending on institutional context.

Two pairs of chief academic officers and chief student affairs officers described their campuses’ efforts to help students think about their many callings in life. In the session “Calling across the (Co-)Curriculum: Academic and Student Affairs Collaborate to Foster Vocational Exploration,” senior administrators from Lee University (TN), Mike Hays and Debbie Murray, and Furman University (SC), Ken Peterson and Connie Carson, provided detailed accounts of the programs that they have developed to encourage students to think deeply about their futures.

The contrasts between the two institutions demonstrated how capacious the language of “calling” and “vocation” can be in providing guidance to undergraduate students. For example, Lee University is a strongly faith-based institution, while Furman is largely secular in focus. The two senior administrators at Furman have worked together for many years and its integrative programs are well established, while those at Lee have only just begun to institute new programming for students and to establish deep cooperative relationships between academic affairs and student affairs. Nevertheless, both universities have recognized that students respond well to curricular and co-curricular opportunities to think about their future directions in life in terms of exploring and discerning their callings.

A focus on calling and vocation can be implemented in various ways, depending on institutional context. Furman has opted for a strategy of breadth, with a “Pathways” model that covers the entire arc of the student experience across four years, while Lee is experimenting with a focus on the sophomore year as a critical juncture for students to think more seriously about their future direction. In both cases, a key factor in the success of the programs has been close cooperation between academic affairs and student affairs, so that students experience greater coherence between their curricular and co-curricular experiences. Still, panelists from both institutions agreed that students are not always aware of the significance of the skills and experiences that they are gaining through the program. As Hayes, Lee University’s vice president for student development, remarked, “When students go home at Thanksgiving break and are asked what they’ve learned in their general education courses, they tend to say, ‘nothing in particular’—when in fact they have gained a great many transferable skills through their conversations about vocational exploration, both within and outside the classroom. We need to do a better job of helping them understand what they are gaining from this kind of work.”

Programs at both institutions were developed in part through grants from CIC’s Network for Vocation in Undergraduate Education (NetVUE), which is supported by Lilly Endowment Inc. and member dues. Many of this session’s participants were from NetVUE institutions and offered additional accounts of how the concepts of calling and vocation were being deployed on their campuses. One question from the audience in particular—“How do you define vocation on your campus?”—brought out the wide range of strategies and programs that this language has helped to develop at NetVUE member institutions.